Inside Look: How ‘deep personalization’ steers RBC’s innovation

Banks have spent years trying to foster relationship banking through digital channels, and for Royal Bank of Canada, that means creating a malleable app that morphs, depending on which customers are using it.

“We are in what we call ‘deep personalization’ and really rotating the experience fundamentally around the customers’ needs,” said Rami Thabet, vice president of digital products at RBC. “We don’t do personalization for personalization’s sake. We’ve seen examples where a line of text or label is changed and somebody calls it ‘personalization.’ Our aspirations were a lot higher.”

The bank, which has CA$1.52 trillion in assets ($1.09 trillion), has spent the past year rolling out new editions and features of its app to satisfy a wide variety of customers, including students, investors and small businesses. It’s an approach meant to create tailored banking experiences based on customers’ needs, and it involves putting customers in charge of their own financial destinies.

Different experiences, not apps

RBC last summer rolled out Mobile Student Edition, a version of its app for young customers that features financial literacy tools, peer-to-peer payments and a carousel that lets users toggle between various accounts. Around the same time, RBC also launched a small business version of its app that offers spending analysis. In April, the bank doubled down on its strategy with the debut of an investment edition for clients to guide their own investing. Rather than developing different apps for each of these customer segments, the bank facilitates customers toggling between the app’s specialized editions and the original version.

“Young adults have a funny habit of growing up,” Thabet said. “When they do grow up, it doesn’t make a lot of sense for us to ask them to download a new app.”

But creating a malleable banking app can be a complex process, often hindered by integration, product development and application delivery, according to Peter Wannemacher, principal analyst of digital banking at research firm Forrester.

“Beyond that, many banks struggle mightily with internal problems like organizational structure and bureaucracy — not to mention internal politics — which make it difficult and painful to pull this off,” he said. “The unfortunate result is, way too many banks have a whole bunch of different stand-alone apps.”

The features in the RBC app versions are all housed in the bank’s flagship app, with the specialized editions featured more prominently for relevant customers. For example, small business owners looking to manage their business finances likely don’t need peer-to-peer payments front and center, Thabet explained, so cash positions and potential upcoming expenses are featured instead.

Understanding what mobile banking features are most relevant to a given customer segment, however, is easier said than done.

According to Thabet, a major aspect of RBC’s product development is bringing in target customers to learn from them. When developing the Mobile Student Edition, for example, the bank brought in about 400 young adults between 14 and 22 years old for focus groups, creation sessions and reviews.

“We engage our clients through co-development and co-design processes, and we work with them quite extensively,” Thabet said. “They really guided the process. They were amazing at busting some myths we had.” For example, the bank learned its younger customers take money seriously and are not interested in an entertainment-focused app that incorporates social media.

As the industry watched JPMorgan shutter its millennial-friendly stand-alone banking app Finn last summer, only one year after launching, it signaled that big banks spinning up finance apps outside of their primary banking app might not be the most elegant and user-friendly solution to personalization. Royal Bank of Scotland and its subsidiary NatWest shut down the stand-alone app Bo earlier this month while Wells Fargo’s digital-only Greenhouse has stalled on its way to a national rollout slated for the end of 2019.

The solution may be so-called “super apps” that combine various customer segment-specific features in a single app, but that strategy comes with its own challenges. As RBC launches new editions and tools within its mobile app, the bank must be careful of overwhelming customers with too many features. Although RBC’s different editions help prevent this overload, banks continue to grapple with how to add mobile functions in a customer-friendly way.

Avoiding the hype trap

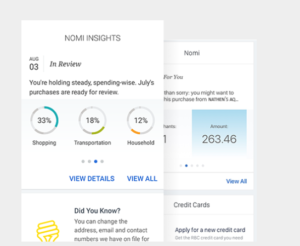

RBC’s relationship banking strategy extends beyond the different editions as the bank has also focused on expanding the different use cases of its digital assistant, NOMI.

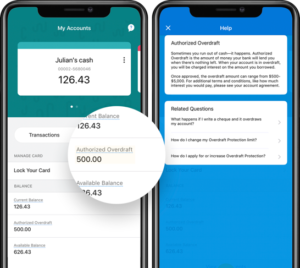

Most recently, the bank launched “Ask NOMI” in response to customers’ financial uncertainty amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The interactive function that allows customers to ask questions about spending has already answered more than 1 million questions since its March launch.

In addition, RBC developed NOMI Budgets last year to help customers control their finances through the app. In 2017 the bank initially rolled out NOMI Find & Save, an automated savings tool, and NOMI Insights, a spending analysis tool for consumers, which was extended to small business clients in October.

Underpinning NOMI’s functions is technology from the data-driven personalization vendor Personetics, which works with the likes of U.S. Bank, Ally and Huntington. The company pulls transaction data from deposits, cards, payments and loans to train its algorithms, according to Jody Bhagat, president of Americas at Personetics. Using six months of historical data, the company’s platform determines the most relevant insights to put in front of a customer accessing a bank’s mobile app.

Although Personetics works with some of the biggest banks in the country, Bhagat said RBC stands out because it avoids innovation for innovation’s sake. “Digital innovation is fraught with companies that do something because someone else is doing it, and it’s not necessarily grounded in customer needs or vision,” he said. RBC’s product development is grounded in research around customer needs, according to Bhagat, and the bank’s co-creation sessions with target customers ensure there is an appetite for the bank’s new features.

RBC is not alone in its offering of an AI-powered chatbot. Capital One has Eno, Bank of America has Erica, and U.K.-based TSB Bank recently launched its “Smart Agent” in a mere five days with the help of IBM.

Banks have invested years and dollars into the development of branded virtual assistants, an industrywide trend that has cruised on the coattails of self-service tools made mainstream by tech giants, like Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri and Google Assistant.

“There was definitely a multiyear period where digital assistants were overhyped and we still see some banks acting as though chatbots and virtual assistants are a cure-all,” Forrester’s Wannemacher said. “But there is now a crop of AI-enabled digital assistants, including RBC’s NOMI, that are genuinely unlocking value for customers and driving improved business outcomes for banks.”

See also: Adoption of digital banking jumps at RBC

The key, however, comes down to the call-to-action embedded in these insights and making that functionality available for a customer who chooses to take action.

“If a bank says, ‘You could safely move XX dollars into savings, but then provides no way to actually accomplish this, or makes doing so inconvenient, then all the AI-based insights in the world are basically useless,” Wannemacher said. “Overall, RBC’s NOMI is one of the strongest types of these services that we’ve looked at around the globe.”

As banks look outside to competitors and other industries for ways to strengthen relationship banking, Wannemacher said financial institutions across the industry should think about embracing ecosystem thinking. For many, this will come down to an “important, and so far rare, shift in a bank’s strategy that recognizing external developers are now crucial customers,” he said.

In RBC’s case, multiple “editions” of a mobile app and digital assistants are two areas of digital banking ripe for exposure to a wider ecosystem of developers, platforms and services that exist outside a bank’s own virtual walls, Wannemacher said.

While RBC’s work with its technology vendors is part of its “magic sauce,” Thabet said the collaboration comes with its own set of challenges that will need to be improved upon in the future. “We start with an ideation process, and often ideation starts with our partners or with us. We go back and forth,” he said. “It’s a very creative, and yet messy, process. I wish it were linear.”